Daniel Horwitz’ Memphis Law Review Article on Fourth Amendment Receives National Recognition

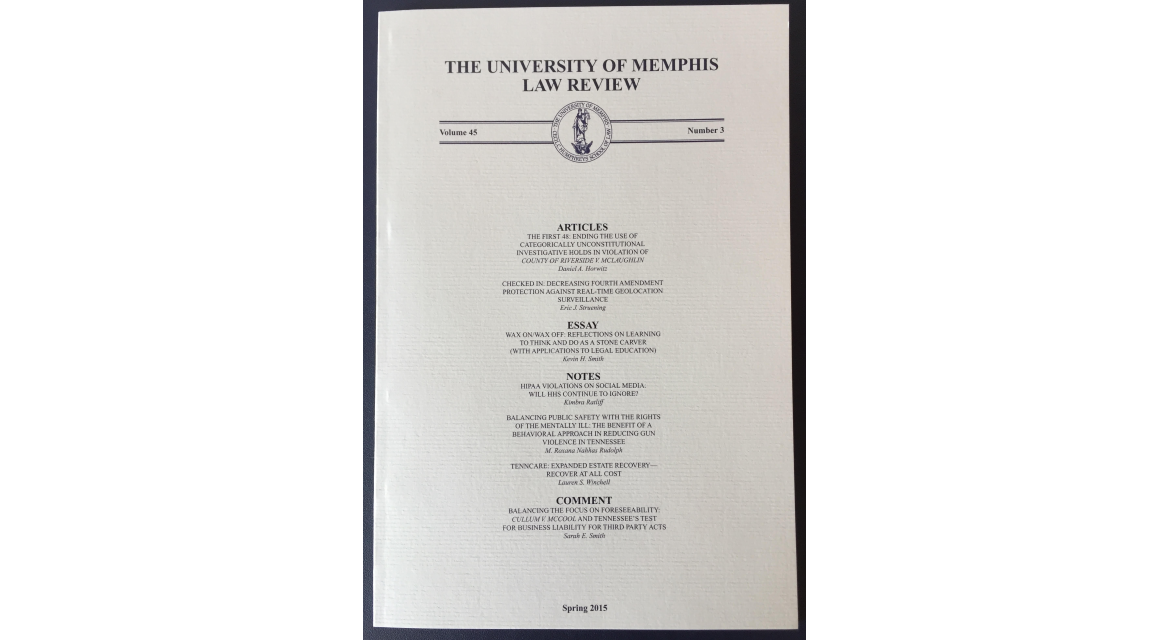

Nashville attorney Daniel Horwitz’s Memphis Law Review article: The First 48: Ending the Use of Categorically Unconstitutional Investigative Holds in Violation of County of Riverside v. McLaughlin, 45 U. Mem L. Rev. 519 (2015), has been selected as a “must read” publication by the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers’ (NACDL) The Champion magazine and the Getting Scholarship into Court Project. Since its publication, the article (accessible here) has also been cited in multiple filings before the United States Supreme Court and by preeminent Fourth Amendment scholar Wayne LaFave.

Nashville attorney Daniel Horwitz’s Memphis Law Review article: The First 48: Ending the Use of Categorically Unconstitutional Investigative Holds in Violation of County of Riverside v. McLaughlin, 45 U. Mem L. Rev. 519 (2015), has been selected as a “must read” publication by the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers’ (NACDL) The Champion magazine and the Getting Scholarship into Court Project. Since its publication, the article (accessible here) has also been cited in multiple filings before the United States Supreme Court and by preeminent Fourth Amendment scholar Wayne LaFave.

Horwitz’s article, published in the Spring 2015 edition of the Memphis Law Review, critiques the holding adopted by a growing number of courts that law enforcement may delay a warrantless arrestee’s constitutional right to receive a judicial determination of probable cause for up to forty-eight hours following an arrest as long as a judge or magistrate ultimately determines that the arrest itself was supported by probable cause. Although this issue has largely escaped review within academic literature, the practice of employing investigative detentions against warrantless arrestees is widespread among law enforcement. Of note, whether such investigative detentions comport with the Fourth Amendment has also generated a circuit split between the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals and one of two irreconcilable lines of authority within the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals. The issue has similarly divided the appellate courts of at least nine states.

Horwitz’s article rejects the notion that law enforcement may ever deliberately delay a warrantless arrestee’s constitutional right to receive a judicial determination of probable cause (known as a “Gerstein hearing”) in order to facilitate further investigation by law enforcement. Specifically, Horwitz argues that the conclusion reached by several courts that police may intentionally delay a warrantless arrestee’s Gerstein hearing for the purpose of further investigation as long as probable cause existed to justify the defendant’s arrest in the first place is inconsistent with the Fourth Amendment for five separate reasons. First, he argues, it confounds the essential distinction between a judicial determination of probable cause, which is a constitutional right, and a determination of probable cause that is made by law enforcement, which carries no constitutional significance. Second, it violates the “administrative purpose” requirement — initially established by the Supreme Court in Gerstein v. Pugh, and subsequently reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in County of Riverside v. McLaughlin — which permits law enforcement to delay a warrantless arrestee’s Gerstein hearing for administratively necessary reasons only. Third, this conclusion fails to grasp the crucial distinction between, on the one hand, delaying a warrantless arrestee’s Gerstein hearing for investigative reasons, and on the other, continuing an investigation while the administrative steps leading up to a warrantless arrestee’s Gerstein hearing are simultaneously being completed. Fourth, it renders McLaughlin’s express prohibition on “delays for the purpose of gathering additional evidence to justify [an] arrest” superfluous, because all arrests unsupported by probable cause are already prohibited by the Fourth Amendment. Fifth, it substantially diminishes the value of the check on law enforcement established by Gerstein by introducing hindsight bias into probable cause determinations and by allowing a substantial number of warrantless arrests to escape judicial review of any kind.

To request a hard copy of the article, please e-mail the author at [email protected].

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Be the first to comment.