Harvard Latino Law Review Publishes Daniel Horwitz’s Article on Undocumented Defendants’ Constitutional Right to Effective Counsel

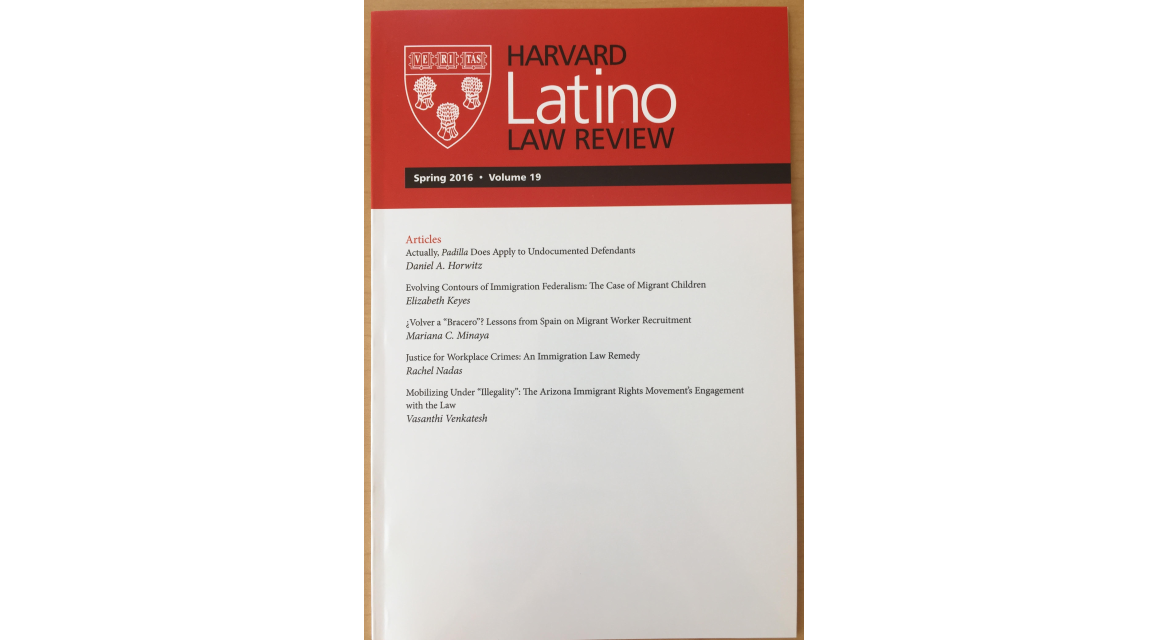

Harvard Law School has published Daniel Horwitz’s article: Actually, Padilla Does Apply to Undocumented Defendants, 19 Harv. Latino L. Rev. 1 (2016), in the Spring 2016 edition of the Harvard Latino Law Review. The article, accessible here, argues that the right to the effective assistance of counsel outlined in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Padilla v. Kentucky, 559 U.S. 356 (2010), applies to undocumented defendants. Its abstract is as follows:

In Padilla v. Kentucky, the U.S. Supreme Court held that non-citizen defendants who plead guilty as a consequence of having received incompetent immigration advice are entitled to withdraw their pleas if they can “convince the court that a decision to reject the plea bargain would have been rational under the circumstances.” To date, however, a nearly unanimous line of authority that includes two U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals, seven U.S. District Courts, trial and appellate courts in four states, and at least one academic scholar has concluded in some form or fashion that “Padilla applies only to those who were present in the country lawfully at the time of the plea.” Specifically, these authorities have reasoned that because “a guilty plea does not increase the risk of deportation” for undocumented defendants, “in a situation where a defendant seeks to withdraw a plea based on Padilla, and alleges lack of knowledge of the risk of deportation, prejudice cannot be established[.]” In other words, these authorities conclude, regardless of either the breadth or the magnitude of their counsel’s incompetent immigration advice, undocumented defendants are never entitled to relief under Padilla because they are categorically incapable of satisfying Padilla’s “prejudice” prong.

These contrary authorities notwithstanding, however, this Article argues that Padilla does apply to undocumented defendants. Four reasons are offered to support this view. First, the contrary conclusion neglects the legal and practical reality that a guilty plea frequently does increase the risk of deportation for undocumented defendants. Second, regardless of the fact that there are myriad situations in which a guilty plea can cause an undocumented defendant to be deported who otherwise would not have been, the test for prejudice under Padilla is not whether a non-citizen defendant would have been deported anyway; instead, the applicable test is whether “a decision to reject the plea bargain would have been rational under the circumstances.” Third, the contention that Padilla does not protect undocumented defendants undermines the underlying purpose of the right to effective assistance of counsel itself: to prevent inaccurate convictions. Fourth, Padilla held without equivocation that: “It is our responsibility under the Constitution to ensure that no criminal defendant — whether a citizen or not — is left to the ‘mercies of incompetent counsel,’” and because this holding expressly includes undocumented defendants, lower courts lack the authority to ignore it.

Taken together, this Article concludes that future courts should reject the prevailing view that Padilla does not apply to undocumented defendants and should hold instead that undocumented defendants’ Padilla claims must be carefully reviewed for prejudice on a case-by-case basis.

Comments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Be the first to comment.